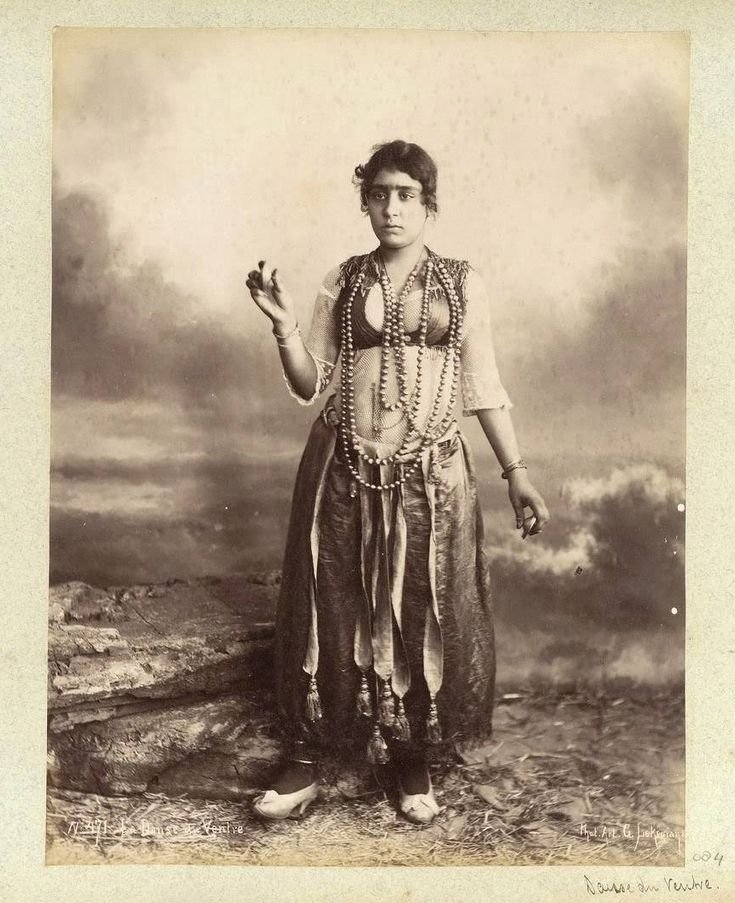

When European travelers arrived in Egypt during the 18th and 19th centuries, they were captivated by the women who danced in the streets — the Ghawazi.

Their movements were hypnotic, their music infectious, and their confidence unapologetic. But instead of seeing them as artists, those travelers saw them as scandalous. And with a few lines in their journals, they turned Egypt’s oldest performance art into a colonial fantasy.

The Real Ghawazi

The word Ghawazi (غوازي) literally means “the conquerors.” Not of land or power, but of hearts.

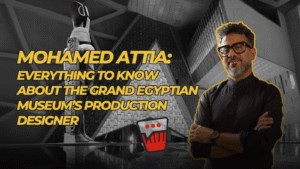

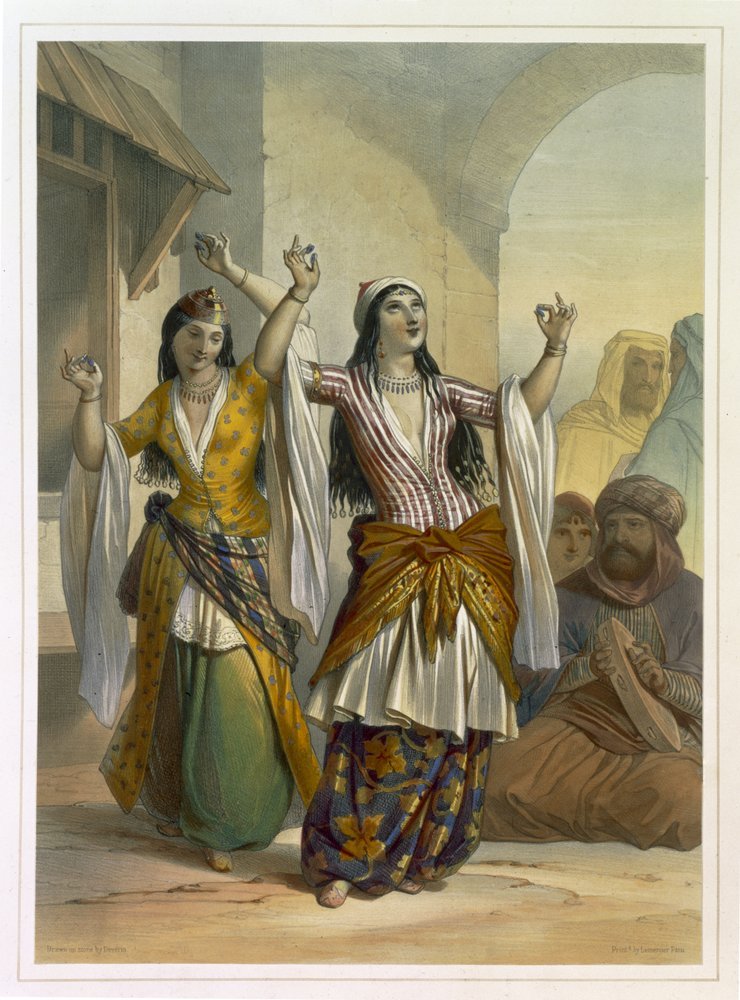

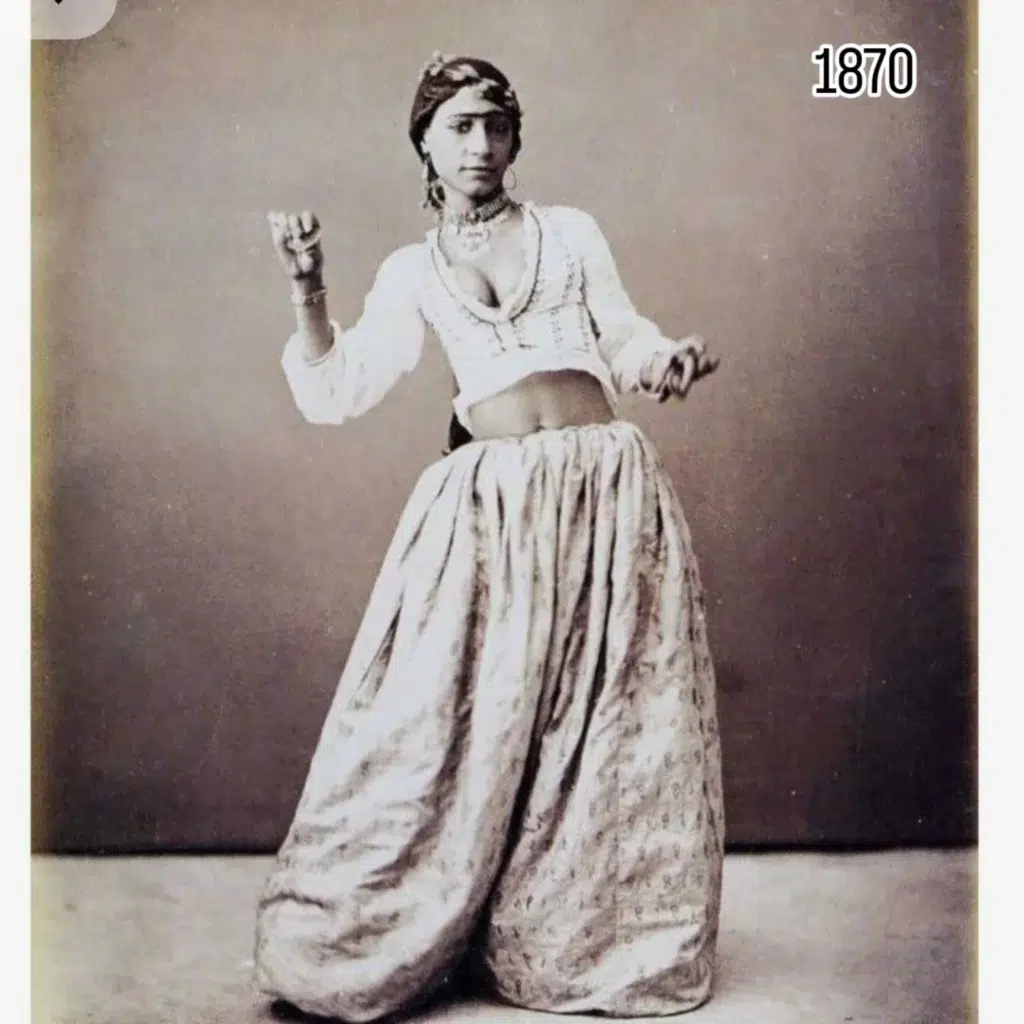

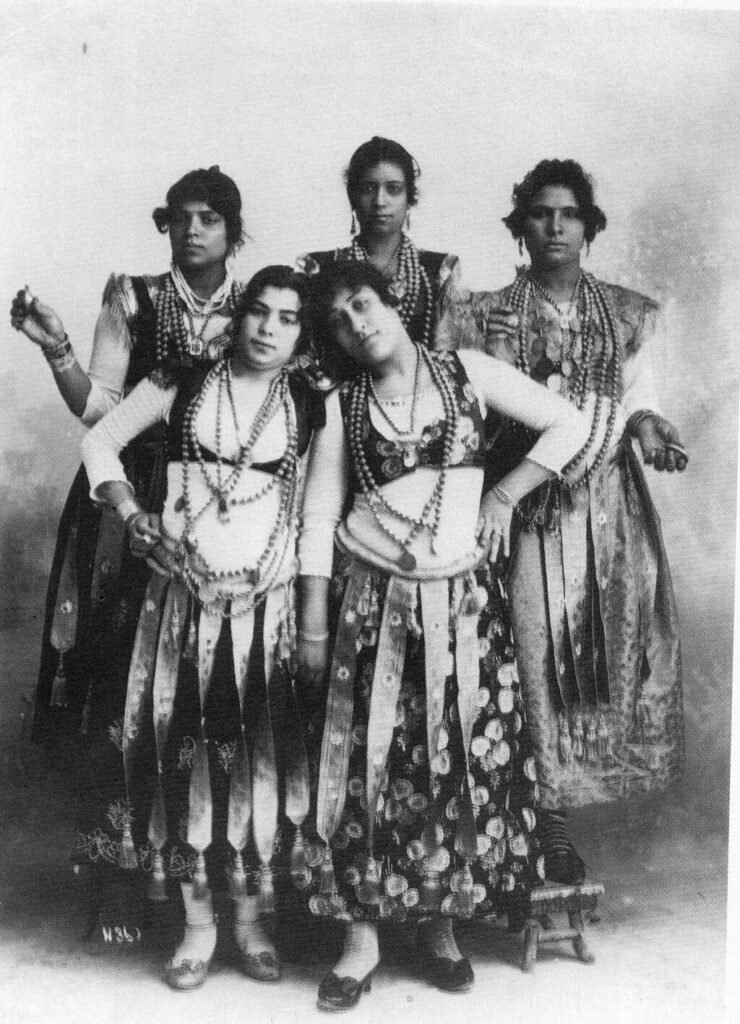

They were female dancers — mostly from Egypt’s Dom or Nawar communities — who earned a living performing at weddings, moulids, and public celebrations. They danced in open spaces, unveiled, often surrounded by live musicians, drums, and the sharp echo of zills (finger cymbals).

Their art was storytelling through movement — full of humor, flirtation, and rhythm. Unlike later cabaret-style belly dancing, Ghawazi performances were raw, communal, and deeply tied to Egypt’s folk traditions. They represented joy, celebration, and survival in a world where women’s voices were rarely heard.

The Dom, known locally as Nawar, is an ethnic group that migrated from India centuries ago and spread across the Middle East. In Egypt, communities were built around music, metalwork, fortune-telling, and dance. Although they were often marginalized, their influence profoundly shaped Egyptian folk art.

The Banat Mazin family from Luxor — particularly Khairya Mazin — are among the last surviving hereditary Ghawazi dancers. Their performances preserve the traditions passed down from mothers and grandmothers who once danced through the streets of Esna and Qena, long after Cairo had turned its back on them.

When Art Became a “Moral Threat”

In 1834, Muhammad Ali Pasha issued a ban on public female dancing in Cairo, forcing many Ghawazi out of the city and into Upper Egypt. The reasoning wasn’t about the art itself — it was about control.

A woman dancing unveiled in public challenged social norms, religious conservatism, and patriarchal authority. Rather than celebrate the culture, authorities labeled it indecent.

But the ban didn’t stop the Ghawazi. It simply pushed them south, where they continued performing for local audiences who still valued their art. Ironically, it was this exile that made them even more visible to foreign travelers who visited Upper Egypt — and that’s when the mythmaking began.

The Colonial Obsession

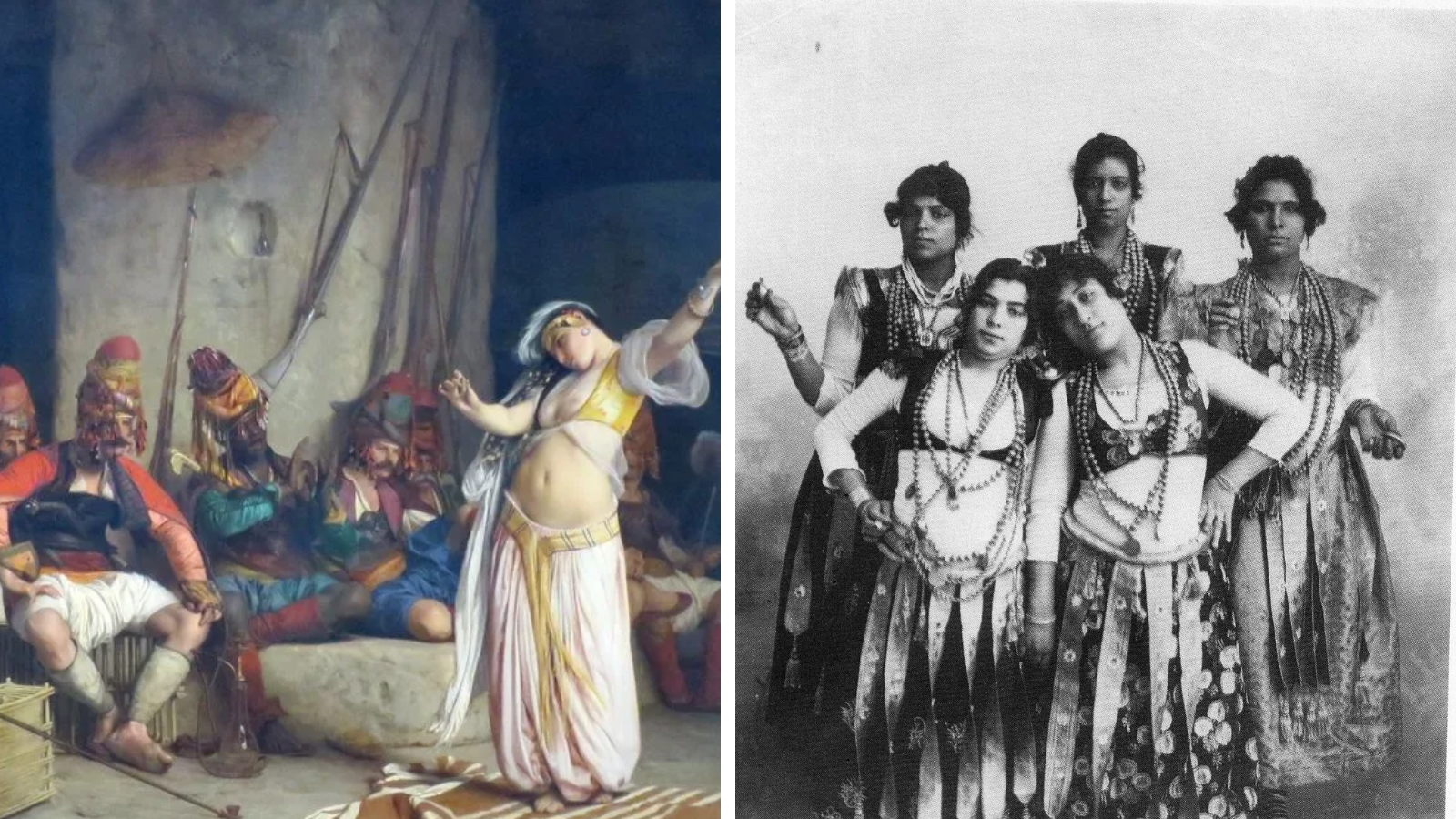

To 19th-century European eyes, the Ghawazi embodied everything “exotic” about the East.

Writers like Edward William Lane and Jacob Burckhardt described them in lurid detail, calling them “abandoned women” and “prostitutes who danced for men.” Their accounts blurred the line between dancer and sex worker — not because it was true for all, but because it fit their worldview.

Victorian men couldn’t fathom women performing publicly, earning their own money, and commanding male attention without being sexually available. So they rewrote the story. In their books and letters, the Ghawazi became the perfect symbol of the “decadent Orient” — sensual, mysterious, and morally fallen.

What these travelers never understood was that most of the Ghawazi were artists, not courtesans. Yes, some might have engaged in sex work, especially after being displaced and stripped of financial stability. But that was a result of economic survival, not identity. To paint all of them with one brush was — and still is — lazy, sexist, and colonial.

The Women Behind the Myth

One of the best-documented Ghawazi families is the Banat Mazin of Luxor.

By the mid-20th century, Khayria Mazin was among the last performers still keeping the tradition alive. Her sisters had retired or passed away, and even she faced harassment from authorities who viewed her art as shameful.

In interviews, Khairya spoke of being pressured by male musicians to join prostitution rings — a sign of how the same patriarchal forces that silenced Ghawazi history still policed their bodies generations later.

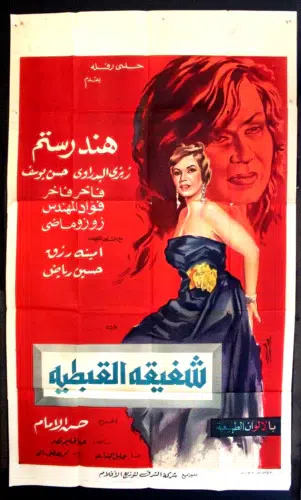

Another legendary name that rose from the same roots was Shafiqa al-Qibtiyya. Born in 1851 to a Coptic family in Cairo, Shafiqa trained under a dancer named Shooq and went on to become one of Egypt’s earliest performing icons. She built a career in Cairo’s entertainment scene, opened her own cabaret, and even introduced the shamadan — the candle-balancing dance that later became a symbol of Egyptian performance.

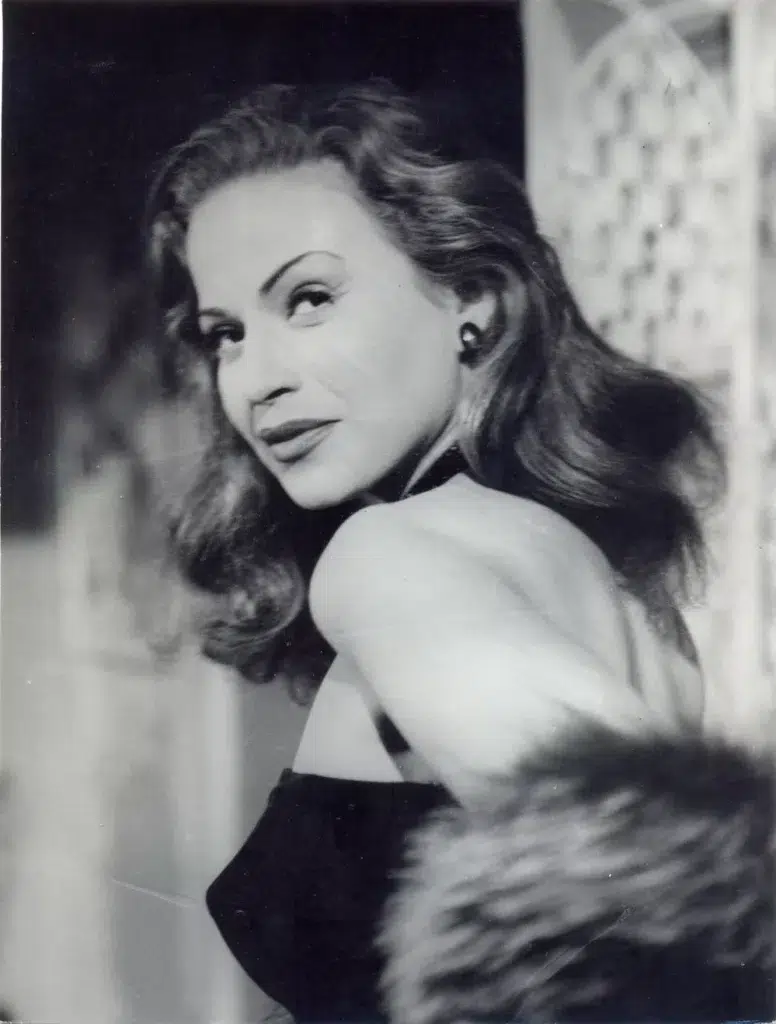

But like many women of her craft, her real story was twisted by time. In 1963, director Hassan El-Imam released the film Shafiqa al-Qibtiyya, starring Hend Rostom.

The movie turned Shafiqa into a glamorous tragic heroine — a woman who rose from poverty to fame and then fell into disgrace. It exaggerated her wealth, fabricated scandals, and flattened her complexity into a cautionary tale.

Worse, the film whitewashed her story. Hend Rostom — light-skinned, blonde, and nicknamed “the Marilyn Monroe of the East” — played Shafiqa, erasing the darker-skinned, working-class roots of the real woman and the Ghawazi heritage she came from. What had started as a story about Egypt’s native performers became a sanitized fantasy that erased the women who built the art form.

The film’s aesthetics reflected the 1960s more than Shafiqa’s actual time — turning a grounded cultural story into an upper-class melodrama. And because cinema is powerful, that version stuck. To this day, many remember Shafiqa through that lens — the glamorous blonde dancer, not the pioneering Ghawazi woman who fought her way through classism, patriarchy, and social hypocrisy.

Europe’s Fantasy, Egypt’s Silence

European Orientalist painters and writers romanticized the Ghawazi into half-naked seductresses, draped in silk, who entertained powerful men in harems that never existed. French colonial artists called it danse du ventre — “dance of the belly” — reducing a rich cultural form to an erotic spectacle.

That imagery sold. It made its way into Parisian cabarets, Hollywood films, and eventually became a part of global pop culture. Meanwhile, in Egypt, the women who inspired it were still being marginalized, banned, or forgotten.

Reclaiming What Was Ours

The Ghawazi weren’t “fallen women.” They were cultural bearers, storytellers, and survivors. Their art carried the rhythm of Egyptian villages, the humor of women’s gatherings, and the resilience of those excluded from polite society.

What colonial narratives did was strip them of their agency and turn them into a spectacle. But if we look closer — beyond the travelogues and Orientalist paintings — we see women who shaped the foundation of Egyptian dance, music, and performance.

Their legacy lives in the hip movements of raqs sharqi, the beats of Upper Egyptian drums, and the confidence of every woman who takes the stage today.

Rewriting their story isn’t just about defending history; it’s about reevaluating it. It’s about giving Egypt’s Ghawazi women back what the colonial lens took from them — their dignity, their artistry, and their place in our cultural memory.