Content Warning: rape, victim-blaming, and spoilers if you care.

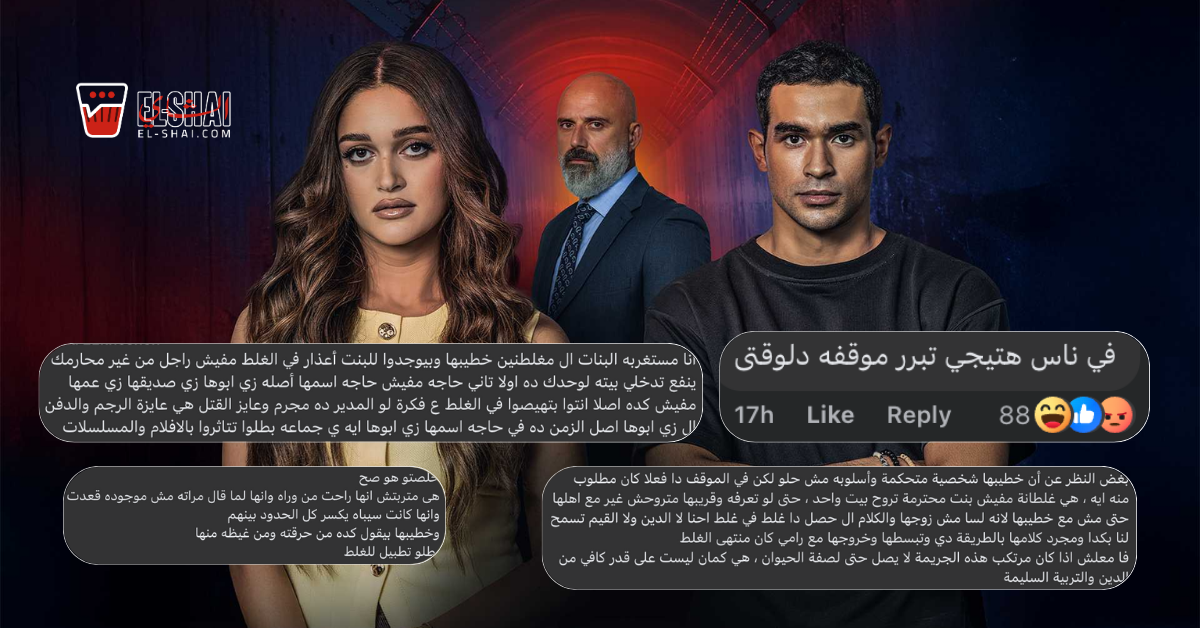

In the Egyptian series Ma Tarah Laysa Kama Yabdo (“What You See Is Not What It Seems”), a recent story, Nour Maksora (“Nour’s Broken”), has left rape survivors drained and furious.

Nour, the female lead, goes to the home of a male friend. He insists his family would be there. Instead, she is alone with him, and he rapes her.

When she tells her fiancé Youssef, his reaction is not comfort, not protection, not rage at the rapist. It is rage at her. He calls her a liar. He blames her for going.

And then he says the most crushing line: “This is what you wanted.”

He breaks off the engagement and walks away, leaving her doubly punished — by violence, and by the man who was supposed to stand beside her.

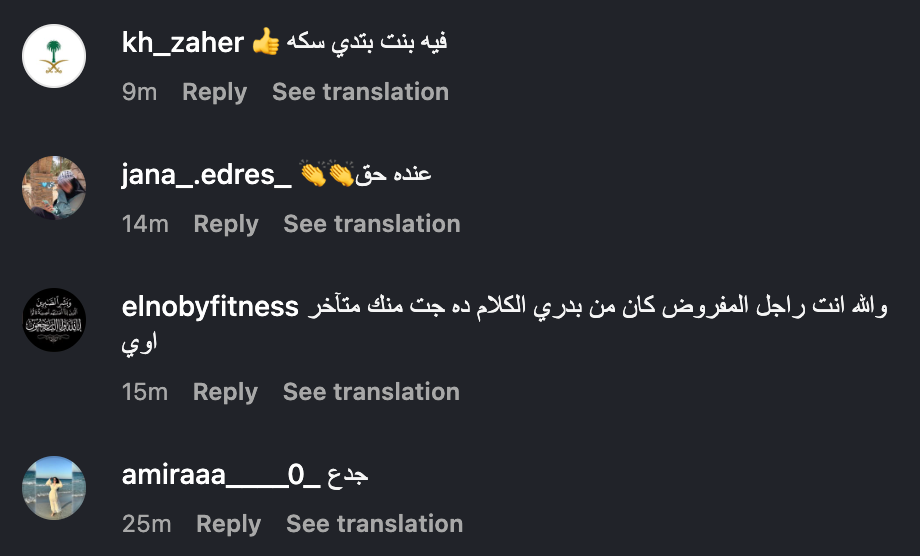

The Comment Section Is the Real Story

Scrolling through the reactions online reveals something horrifying but not surprising: people aren’t condemning Rami. They are condemning Nour.

“Why did she go?”

“Why didn’t she leave once she saw the house was empty?”

“No respectable girl would ever do this.”

The majority of comments fixate on her actions, her morality, her supposed recklessness.

The cultural reflex is on full display: blame the woman, excuse the man.

The Series Knew What It Was Doing

This isn’t a neutral mistake.

Producers and writers in Egypt know the cultural script around rape. They know women are routinely blamed, shamed, and silenced. They knew that showing Nour’s rape this way would spark this exact response. And they still chose it.

Instead of centering the crime — a man raping a woman — the series framed it as a moral riddle: Was she careless? Did she bring it on herself? Should her fiancé forgive her?

That is not storytelling. That is exploitation.

Even if the writers claim their intention was to expose victim-blaming, intent is irrelevant when the effect is to retraumatize survivors and normalize cruelty.

When a rape scene is crafted for shock or titillation rather than truth, it is not told from the survivor’s perspective. It’s filtered through the male gaze.

The Cost to Survivors

As a survivor myself, watching this unfold is not just tiring — it is suffocating. Reading comment after comment attacking Nour feels like watching strangers rehearse the same words that once destroyed me.

It makes me scared to leave my house. It makes me feel like my society will never see me as a victim, only as someone who “asked for it.”

This endless back-and-forth isn’t a debate. It’s retraumatization. It confirms that if women come forward, they will be interrogated for every choice they made instead of being met with compassion.

Drama Has a Responsibility

Egyptian drama has power. Millions watch these shows. Writers cannot hide behind “we’re just telling stories.” Stories shape attitudes. Stories normalize.

This isn’t Switzerland, where audiences have a baseline understanding of rape as a crime. This is Egypt — a country where female genital mutilation is still defended as “good for women,” where raped girls can be killed by their families in the name of “honor.”

When you drop a rape scene into that context without clearly condemning the rapist, you’re not educating anyone. You’re feeding the reflex to blame the victim. You’re handing ammunition to the very culture that already shames women into silence.

And that is unforgivable.

We Refuse This Frame

Rape is not a debate. It is not a moral test for women. It is not a plot twist for ratings. It is a crime.

When TV blames the victim, it becomes the rapist’s accomplice. When it gives men lines like “this is what you wanted,” it doesn’t just reflect the culture — it reinforces it.

Women in Egypt cannot afford this. Survivors cannot afford this.

If the industry wants to be brave, it should show the truth: the blame is always, only, on the rapist. And the cost of pretending otherwise is women’s lives, safety, and ability to exist freely in their own country.

Rape is violence. It is never the woman’s fault. And any series that suggests otherwise is complicit.

No One Asks for Rape – And It’s Irrelevant What Caused it!

Writers, producers, and networks in Egypt must adopt ethical guidelines when depicting sexual violence. Survivors should be consulted. Sensitivity readers should be hired. Storylines should be vetted for harm, not just ratings.

Because what you show on screen doesn’t stay there.

It echoes in living rooms. It spreads in comment sections. It lodges in the minds of girls and women who are still learning what kind of treatment they deserve.

If Egyptian media wants to claim courage, it must stop sensationalizing women’s pain.

It must start telling the truth.

How the rape happened should never be the focus of the conversation.

This article deeply resonated with me. It’s powerful to see the real-world impact of victim-blaming narratives in media. The way Nour is portrayed is infuriating and heartbreaking, highlighting the urgent need for more responsible storytelling that centers survivors, not perpetrators.