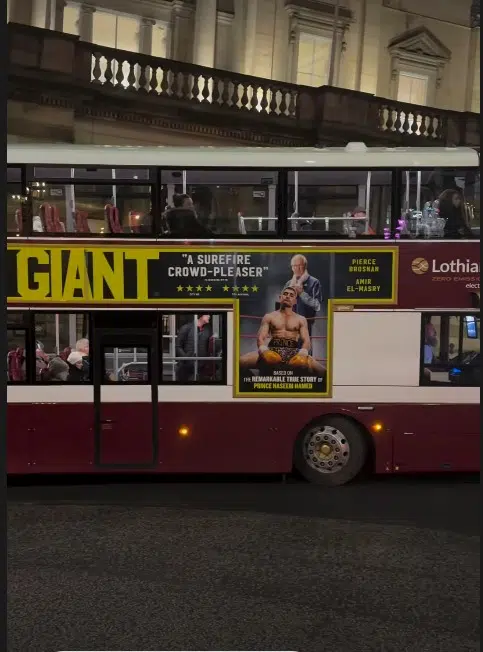

We used to celebrate when Egyptian actors landed blink-and-you-miss-it roles in international films. Today, we have Amir El-Masry front and center on posters promoted across the UK. That alone feels like a cultural shift worth acknowledging.

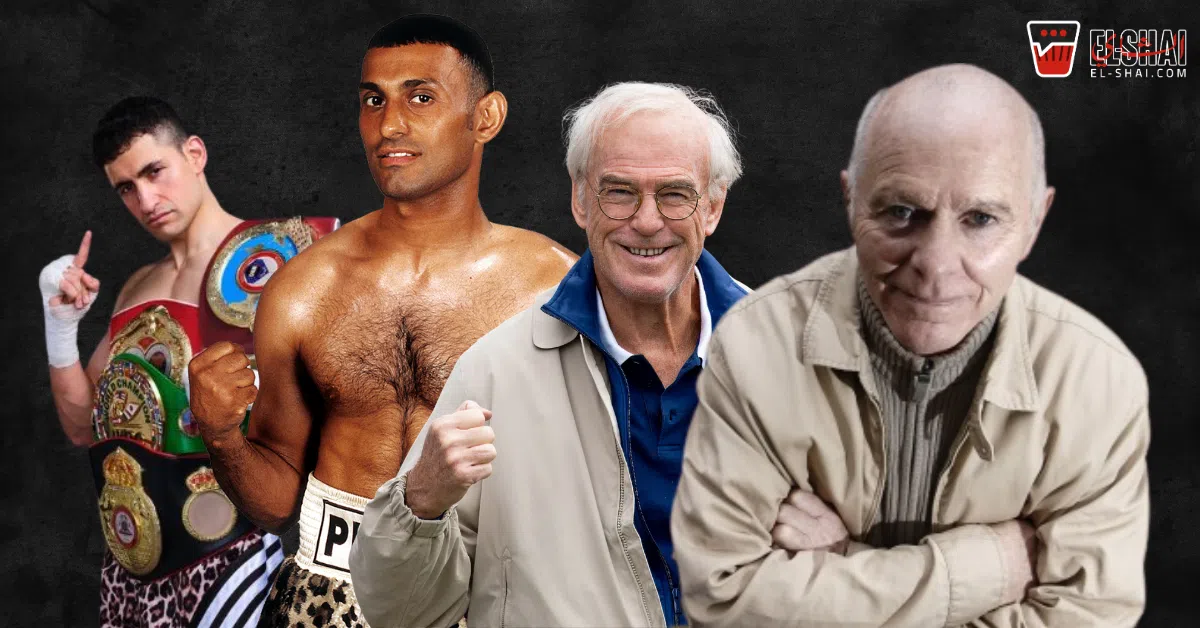

This is for the international release of Giant, a film inspired by the complicated real-life relationship between boxer Naseem Hamed and his trainer, Brendan Ingle. El-Masry plays Hamed, while Pierce Brosnan steps into the role of Ingle.

I’ll be upfront: I’m biased. I’ve been a fan of Amir for years, professionally and personally, and Brosnan is my Bond. Sean Connery may be the most historically “successful,” but for anyone who grew up in the 90s, this argument doesn’t really exist.

The short version of this review: go watch it. Not because it stars an Egyptian actor, but because it’s actually a good film, even if it isn’t flawless.

The real story behind Giant

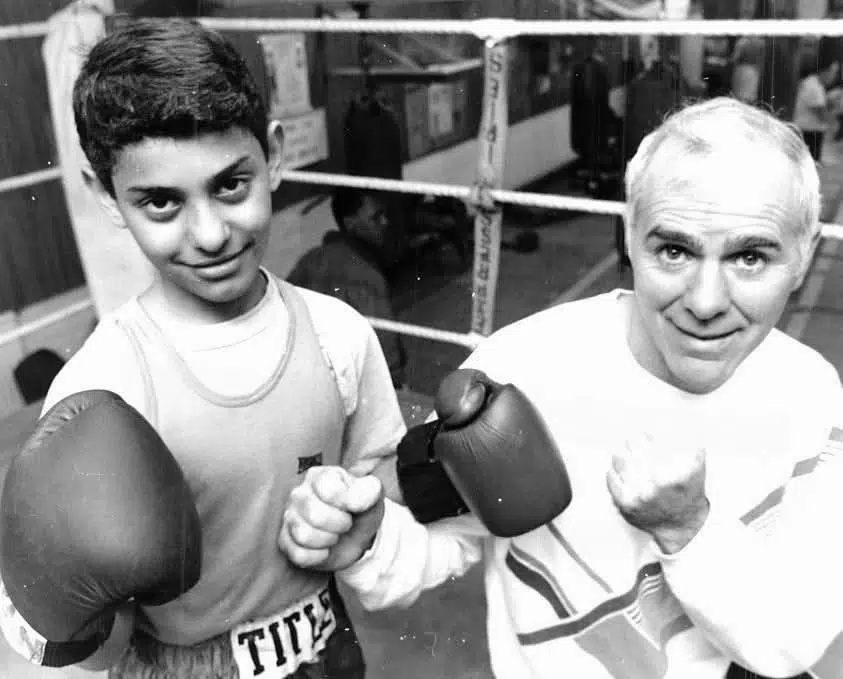

Naseem Hamed was one of the most polarising figures in boxing history. Born in Sheffield in 1974 to Yemeni parents, he rose from a working-class immigrant background to global fame in the 1990s, driven by raw talent and unapologetic confidence. At the center of that rise was Brendan Ingle, a relationship the film makes clear was never just trainer and fighter.

Ingle was a father figure, a gatekeeper, and a stabilising force. From a young age, he shaped Hamed’s boxing identity, allowing his unorthodox instincts to flourish within a strict structure. That balance worked as long as authority and trust remained intact.

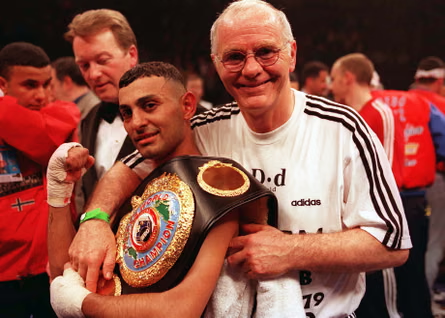

Once fame, money, and entourage culture entered the picture, the dynamic shifted. Hamed became more than a fighter; he became a brand. Ingle, however, did not evolve. Discipline, humility, and control remained non-negotiable, while Hamed increasingly experienced them as limitations rather than protection.

Their split wasn’t the result of one argument, but of fundamentally different ideas of success. Ingle believed Hamed’s talent only survived within structure. Hamed believed his success proved he had outgrown it. When he walked away, he didn’t just leave a trainer; he left the framework that made his brilliance sustainable. The film treats this not as betrayal, but as a tragedy rooted in timing.

Casting risks that paid off

Brosnan captures Ingle with unsettling confidence. While many viewers may not be deeply familiar with the real man, Hamed himself has said in multiple interviews that Brosnan portrayed Ingle almost perfectly, admitting the performance stirred unresolved emotions. That endorsement carries weight.

Amir’s casting, on the other hand, initially felt risky. Anyone who grew up in the UK, Europe, or the Arab world during the 80s and 90s knew Naseem Hamed intimately. We watched him grow up in public. We also know Amir. He grew up on our screens, and while his early roles carried swagger, none prepared us to see him as a boxer, let alone that boxer.

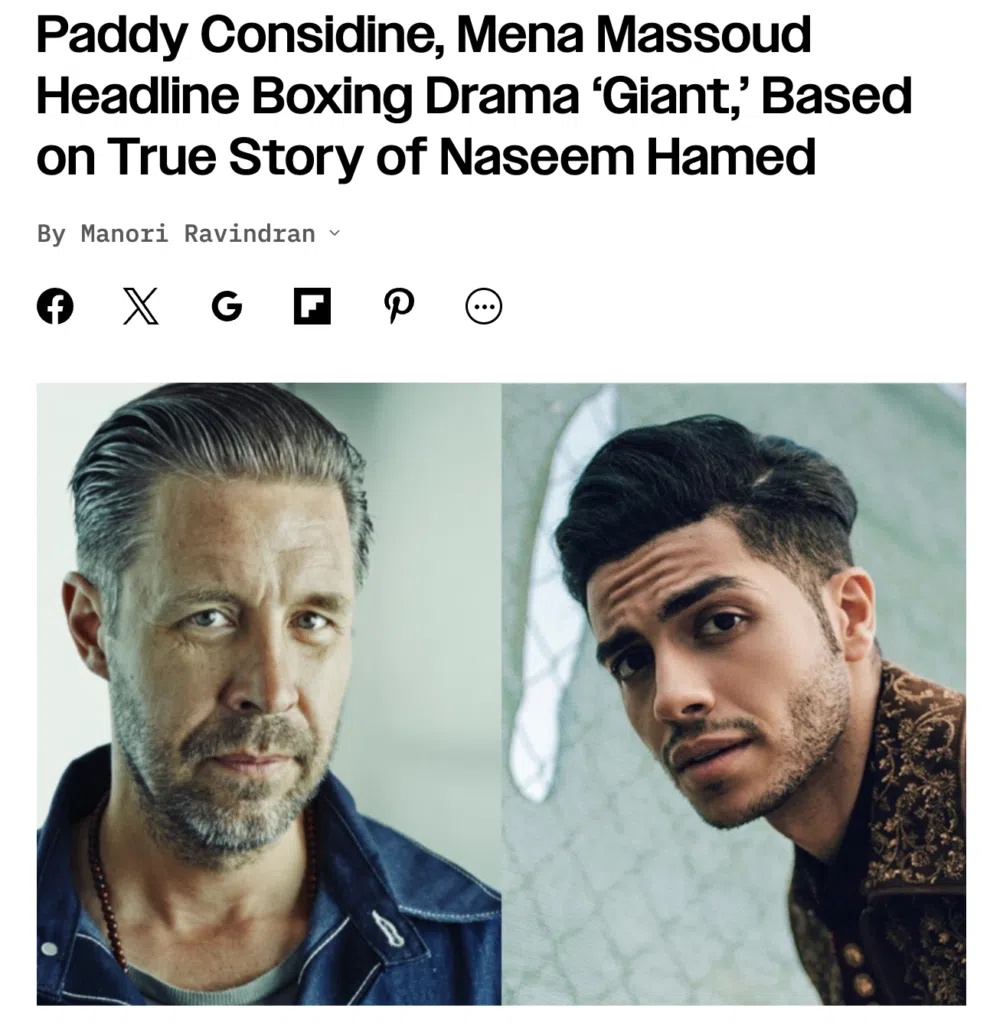

Physically, the resemblance wasn’t obvious either, especially considering Mena Massoud was reportedly an early choice for the role. Still, Amir delivers. Not through imitation, but transformation. There are moments where you genuinely forget you’re watching a performance. He plays Hamed as a volatile mix of talent, ego, vulnerability, and charm, not a caricature.

Ali Saleh, who portrays Naseem in his youth, deserves equal praise. His scenes feel alive and grounded, offering emotional clarity without sentimentality.

Music, movement, and momentum

Technically, Giant mostly knows exactly what it’s doing. The music and song choices are sharp and intentional, functioning almost as a character of their own rather than background filler. They carry emotion and tension without spelling anything out.

The cinematography follows the same logic. Certain angles are deliberately uncomfortable, even stressful, mirroring the volatility of the relationship and the chaos surrounding it. That visual tension works. The film’s rhythm is also well judged, moving between fast, high-energy sequences and slower, quieter moments. Those shifts keep you engaged without exhausting you, allowing the story to breathe when it needs to.

The one truly unforgivable misstep, however, is the CGI. It’s distracting, unnecessary, and pulls you out of moments that would have been far more powerful if they had been left practical or simply implied. In a film that thrives on rawness, the CGI feels like a solution to a problem that didn’t exist.

The discomfort is the point.

Where the film becomes uncomfortable is also where it becomes most interesting. There’s an undeniable white-savior framing in how Ingle is portrayed, and Naseem’s faith as a Muslim is often reduced to surface-level moments. But that discomfort feels intentional.

This isn’t a film about Naseem as he saw himself. It’s about Ingle and how he understood his role in the story. Ingle genuinely believed he saved a young brown Muslim boy from himself. That belief shaped their relationship and, ultimately, its collapse.

In real life, their fallout was also deeply financial. Ingle maintained the deal he made with Naseem when Naseem was a child, long after Naseem became an adult and a global star. To this day, Hamed insists he was financially exploited. The film doesn’t fully unpack this, but it hints at it through Ingle’s pride and self-mythologising.

No heroes, no saints

Importantly, the film doesn’t sanctify either man. Naseem’s ego, selfishness, and tunnel vision are laid bare. Ingle’s rigidity and need for control are equally exposed. No one is absolved, and no one is crowned a hero.

Even in a biopic where the outcome is known, Giant allows itself one imaginative ending. That final choice doesn’t offer closure so much as it poses a question: how do we decide who was right and who was wrong when both believed they were?

That ambiguity lingers. And it’s why Giant works.

Giant is a solid 8/10, and it’s a must-watch not just for boxing fans, but for anyone looking for a smart, accessible, thought-provoking film that doesn’t rely on superheroes, massive budgets, or spectacle to justify its existence. Giant proves that intimate, character-driven stories still have a place in cinemas.

The film is now showing in Egyptian and international cinemas.